Creativity As Survival Skill

Last week, a colleague lamented to me the rut that so many congregations and fellow pastors seem to be stuck in. Our denomination is melting down, with a number of churches disaffiliating and many more forced into votes by disgruntled members. And this while living through the aftershocks of the pandemic, the toll of which has yet to really be assessed in terms of our collective spiritual health. She told me that, in order to deal with the constant demands, we’ve unintentionally shut down other processes.

“No one seems to be able to create anymore,” she said. “All the grief and stress have sucked that out of us.”

It’s not a surprising statement, at least not to those who know a thing or two about what stress does to you. Negative emotions put blocks on the processes that help us think and feel. They sap us of our ability to understand complexity or make good decisions. We have a harder time seeing solutions—particularly ones that require a bit of mental and emotional construction.

That’s easy enough to see when it’s all just academic principle. When you’re the one in the stew, however, it’s hard not to be boiled into mush.

My colleague said that stress and grief has eaten away our creativity, and she’s right. You might think the solution to that problem, then, would be to resolve the stress and manage the grief and get our creativity back. I suppose that’s a reasonable way to go about it.

A reasonable way. Not the only way. In fact, I think reversing that formula is more helpful. Here’s why.

In April of 2016, I got sick at a youth event our campus ministry students were leading in Pierre, SD. What I thought was a stomach bug worsened to the point that I lay doubled over in pain in my hotel room, unable to play with the band or even come watch. My friend Cody had to take me to the ER. Another friend, Sam, drove me back to Mitchell. I could barely hold my eyes open.

I spent the rest of that year in and out of the hospital. By the time they diagnosed the problem (ulcerative colitis), I’d lost 40 pounds—far too much for a person my size to drop—and spiraled into depression. It sucked in every conceivable way. I still don’t like to remember it.

It’s hard to say what led to that illness popping up at that particular time. Most people with UC are diagnosed much younger than I was, and many of those realize they’d had symptoms for years before getting the pronouncement. Mine came on nearly overnight. The only two things I know for certain that played a part are my genetic code and the stress of the previous two years. As the adage goes, the body keeps the score.

Similarly, the road back to health was paved with many kinds of stones. Changing diet helped some, and the meds made a big difference. As my body recovered, my brain had more resources with which to cope. I’ll probably never fully appreciate the load my family and friends carried during those months.

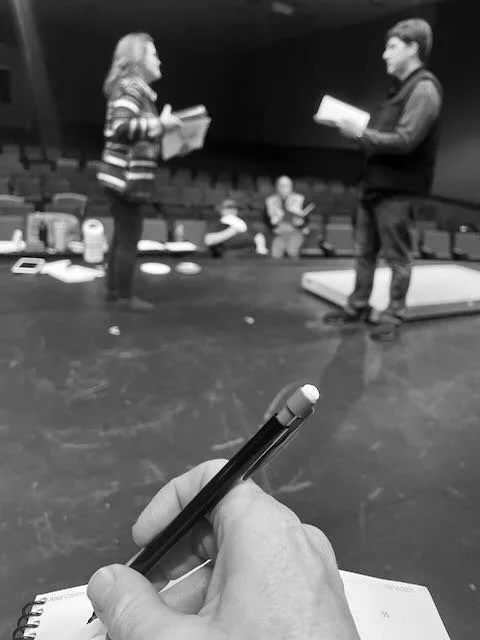

One big stone along the path to recovery turned out to be the Mitchell ACT (Area Community Theater). I hadn’t been on stage for nearly two decades when I saw the call for auditions for a production of Sleepy Hollow. But in the early fall of 2017, mostly recovered from the worst of my illness, II dove into acting and building set and relearning how to be part of this form of storytelling. I remembered what incredible power there is in laying your worries at the rehearsal door and working hard to create a moment to share with an audience that won’t show up until weeks later. I found myself asking why this awful thing? less and why not this wonderful thing? more.

Six years and countless shows since I last wore Ichabod Crane’s three-cornered hat, ACT is once again at the heart of recovery—this time from the dumpster fire that began 2023 for me and my family. Whether it’s rehearsing music or learning choreography or building set, when I step into the theater I know I’m there to create alongside others. My part is not the most important, but it is nonetheless essential. If we’re going to wow audiences with You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown in early May, I have to be ready to roll up my sleeves and focus on the task at hand.

It’s amazing what simply rehearsing a play has done for my soul.

To me, creating is not the byproduct, but the medicine itself. Writing, sketching, acting, playing music, singing, woodworking—these are all things that require significant focus to do well. When I get lost in one of them, my brain has a chance to shut down the worrying sectors for a bit and let the creative ones take over. And if, at the end of one of those sessions, I’m pleased with the outcome, I get that little hit of good feeling that comes with making something you know your grandma will hang on her fridge.

I used to think that maybe suffering was necessary to art—that no one could really produce anything worthwhile unless it came through tremendous pain. The painter whose inner demons only rest when he’s working. The pianist who forgets her arthritis only when she’s playing. The writer who can only make sense of the actual world by letting characters roam in a fictional one. History has plenty of examples of tortured souls producing great art.

ButI think that’s an incorrect—or at least incomplete—reading of the evidence. It’s not that pain is essential to art, but that, for some of us, anyhow, art is essential for surviving pain.

The more we get into rehearsals for You’re a Good Man, the better my body feels. I’ll always be an atrocious dancer, but I no longer hurt when I move. I can enjoy being with the cast and crew without faking it. I can sing without fear of blowing a note. When I’m away from the theater, I write more. I sleep better.

I remember Andy Crouch saying that the only way to change culture is by making more of it. Perhaps a similar thing is true for church. Maybe also for our lives—that the only way to change them is by building new onto what’s already there. It can’t hurt to try.

After all, creativity is a survival skill. It offers a way out of suffering and a path to healing. It helps us, at last, become human again.